I Have Been Taking Notes Wrong, and You Probably Do Too

in Blog

A Physical Zettlekasten — Image from Wikipedia

I am a bookworm, and over the years, I have read and logged nearly 200 books. However, I must admit that for many of the books I read, what little remained in my head are some general ideas of what the book is about. Surely, if I want to remind myself about a particular one, I can just read the book’s summary, which is readily available online nowadays. But those words are not written by me, and thus the knowledge is never my own.

I stumbled on the concept of Zettlekasten (German for slip box) a couple of weeks back, and this idea really intrigued me. Instead of only storing, organizing, and connecting information in one’s head, the idea is to use an external structure, a scaffold, outside of your primary brain to help with this process. Basically, it is the equivalent of building a second brain, which is far less likely to forget or err.

This led me down the rabbit hole of searching for new tools, reading articles, and watching Youtube videos. I eventually stumbled on a book titled “How to take smart notes” by Sönke Ahrens, with a pretty good review, and decided to give it a read. This is my review of this book and how it changed me.

Niklas Luhmann and his slip box

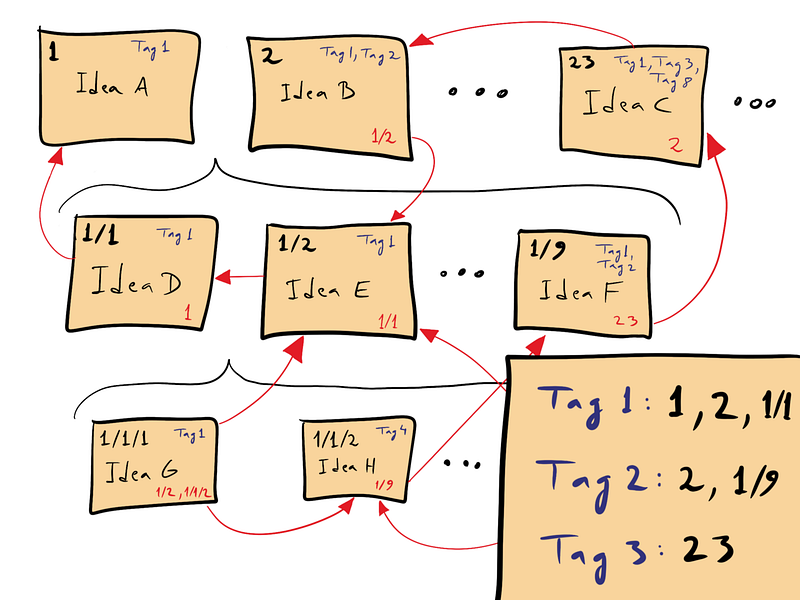

Illustration of the slip box method — Image from Wikipedia

Zettlekasten was developed by Niklas Luhmann, a famous German sociologist. He started his career as a lawyer and spent his hours after work following his interests in philosophy, organizational theory, and sociology. His old note-taking method of writing down notes on book margins was not working, so he invented a highly effective system.

The slip box system he developed led him to a position in academia as the professor of sociology at the University of Bielefeld, an amazing feat for an academic outsider like him. He also wrote 90,000 notes in his physical slip box and published 58 books in 30 years.

The word Zettelkasten is German for “slip box,” which refers to a box containing many slips of paper (Ahrens, 2017). Each slip is an idea that connects with other ideas using a linking system, much like hyperlinks in our digital world.

Who should read this book

You should read this book if you are:

- A student

- A researcher

- A writer

- A book worm

Or if you want to create a Personal Knowledge Management System.

This book in 3 sentences

Taking note the wrong way is no better than not taking note at all.

Photo by ConvertKit on Unsplash

We have all done it. Whenever we want to remember something, we take notes. I have notes everywhere, thousands of notes on my phone, notes on the margin of the books I read, notes on notebooks and scrap papers. But to be brutally honest, 95% of the notes I took I never look at them for a second time. And yes, to the point of the first sentence, that 95% of the notes ended up not being useful to me.

Taking them notes then feels like a chore rather than an actual productive thing to do. Reading this book, I realized that I took notes like an archivist, taking them so that they will be stored away and never see the light of day. This kind of note is called the fleeting note, reminding you of what you don’t want to forget within a context. The context can be anything from a blog post, meeting, a book, a video, or a lecture. A fleeting note is ephemeral, imperfect, and only used to capture your thoughts.

I have always taken notes in this manner, with a mindset of an archivist and no structure or system to reencounter the notes. I frequently face the blank page problem, not knowing where to start, or not having enough ideas when writing something on Medium. The slip box method offers a solution to this.

Keep a low bar for capturing ideas, but be diligent to review them in a couple of days.

Photo by Markus Winkler on Unsplash

Shortly after taking fleeting notes, I go back and review the fleeting notes to pick out what is really important. I then create literature notes in my own words, with full sentences and references. I try to limit to one idea per note. If I need to define a term, I create a definition note and link to it. I try to recall from memory instead of looking at the source or looking for more information (the latter step is for that).

Doing this process, I found that not all of the ideas I jotted down in my fleeting notes remain relevant. This acts as a filter step for me where I choose what interest, surprise or excite me and develop them into full ideas. I also start thinking about when I will reencounter the notes and develop the idea into a paragraph that I can use for that occasion. Thinking back to the nearly 200 books I read, I could have had a treasure trove of personal knowledge if I follow this practice sooner.

Many researchers have shown that writing plays a central role in learning. Writing demonstrates that one has learned a concept and shows off the ability to think critically and communicate that concept to others. Writing down literature notes in paragraphs is also a way for me to remember the concept longer.

If you want to really understand something, you have to translate it into your own words.

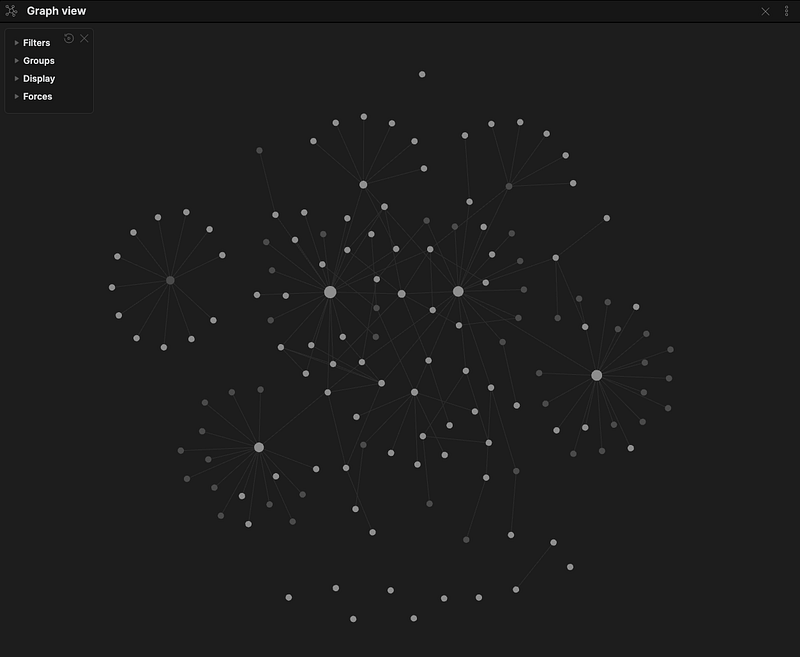

The permanent notes I have so far — Image by the author

The final kind of note in the Zettlekasten method, the most important one, is to make permanent notes. Whereas literature notes are written in the context of the source, permanent notes are written in your slip box, your own ideas and interests. The permanent notes you take are without context. You should write them so that even if you encounter them 10 years later, you know exactly what you meant.

The thing that resembles a human brain is the connections between notes. Literature notes only connect to the source of the idea, whereas permanent notes can have many connections. One permanent note can be linked across disciplines. For example, an idea in Psychology can be linked to customer behavior, data analytics, or economics. You no longer take notes as an archivist but as a writer.

Whenever I put something in my slip box, I always think about what other notes I can link to and how I will reencounter this note. No longer do I face the blank page problem. Now, on my weekly routine of writing an article on Saturday morning, I turn to my slip box and effortlessly put together a draft for a new article.

My top 3 quotes

Writing notes is not the main work. Thinking is. Reading is. Understanding and coming up with ideas is. (Ahrens, 2017)

Every intellectual endeavor starts from an already existing preconception which then can be transformed during further inquiries and can serve as a starting point for following endeavors. (Ahrens, 2017)

A truly wise person is not someone who knows everything, but someone who is able to make sense of things by drawing from an extended resource of interpretation schemes. (Ahrens, 2017)

How this book changed me

As mentioned above, I stumbled on this book when researching the Zettlekasten method. The book does a great job of explaining the concepts and benefits of taking smart notes. There are some good quotes and anecdotes too. However, the “How” in “How to take smart notes” was neglected and can be better developed. There are many other great resources on the internet to take smarter notes like this and this.

Software-wise, I started this journey following the PARA method (Project, Area, Resource, and Archive) put forth by Tiago Forte using Notion. Although Notion is a great software, the process was not fitting for me. I tried out several other ones and currently ended up with Obsidian.

I have no idea if Obsidian will be here to stay, or I will replace it with something else in a couple of months. But I am glad that I took the hardest step, which is getting started on this journey. This is just the beginning for me, and there is much more that I need to learn.

Conclusion

- Take notes with the mindset of a writer instead of an archivist.

- Fleeting notes are ephemeral, imperfect.

- Literature notes are things you don’t want to forget within a context.

- Permanent notes are independent notes linking across disciplines.

References:

- Ahrens, S. (2017). How to Take Smart Notes: One Simple Technique to Boost Writing, Learning, and Thinking — for Students, Academics, and Nonfiction Book Writers.